Returning to their roles six years after the Tony Award-winning revival of August Wilson’s “Fences” stunned Broadway; Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, and Stephen Henderson are at long last presenting the sixth play in Wilson “Pittsburg Cycle” to film audiences.

Returning to their roles six years after the Tony Award-winning revival of August Wilson’s “Fences” stunned Broadway; Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, and Stephen Henderson are at long last presenting the sixth play in Wilson “Pittsburg Cycle” to film audiences.

The play, which was written in 1983 and first debuted on Broadway in 1987 is one of Wilson’s most beloved and well-known from his Twentieth Century Pittsburg Cycle. Set in the 1950’s, “Fences” follows 53-year old sanitation worker Troy Maxson and his family, who are struggling to thrive in the racially tense era. Recently, at a screening for the film in New York City that I attended, Academy Award Winner Denzel Washington who is directing and starring in the film, Academy Award Nominee Viola Davis, and Tony Award Nominee Stephen Henderson, sat down for a post-screening Q&A. They discussed their return to “Fences,” adapting it for film, and what August Wilson’s work means for us today.

Denzel, getting “Fences” to the big screen has been a very long process for you. What did you see in the play that made you realize it would make a great film? I understand that August Wilson wrote the screenplay.

Denzel Washington: In 2009, Scott Rudin sent me August’s original screenplay and asked me what I wanted to do with it. He wanted to know if I wanted to act in it, direct it or produce it. I said, “Well, let me read it first.” (Laughing) So, I read it, and I realized I hadn’t read the play, so I read the play. I had seen the play in the ‘80s, so I thought I was too young to be Troy or too old to be Cory. I was thinking about when I saw it in the ‘80s. And then, when I read the play and it said, “Troy, 53-years old” and I was 55 at the time, I said, “Oh, I better hurry up.” So, it was as simple as that. I called Scott Rudin, and I told him I wanted to do the play, so that’s how the ball got rolling. I never said, “I’ll do the play, and the next year I’ll do the film, I just wanted to do the play.”

When you talk about adapting a play into a film, there is a lot of discussion about opening up the world. For all of you, because you were all in the play, let’s talk about recontextualizing some of the scenes because we are able to move away from the yard in the film.

DW: Well, let me just say before they speak, I never thought about opening it up, I don’t even know what that means, I just thought about where else would it make sense for this scene to take place. I thought, “Why can’t Rose walk in the kitchen?” So we used the front yard, the backyard, the kitchen, we used the front room; we used the porch, we used the front street and upstairs and other places, the back of the [garbage truck], the sanitation yard, the insane asylum, the bar, and that worked well.

Stephen Henderson: It all fit, it really did. Pittsburg fit. Spiritually speaking we knew that we were on streets that August had walked and that he had mused on back when he was just writing. Because he wrote, he wrote before anybody was doing it. So to be in touch with that and to have his family there, it was really rich. The community we were in, they so welcomed us.

Viola Davis: They were so protective of the work.

DW: We had a guy, a gentlemen by the name of Mr. Greenleaf who lived behind the house we were shooting in, and he was like a part of the movie. (Laughing) He would come downstairs, and he couldn’t hear well to say, “Ya’ll want some coffee?”

How did you calibrate this world as a director?

DW: We had depth, and we wanted to take advantage of that cinematically. When you look in one direction where Troy’s chair was, you could see out through the yard across the street, there was an old cork bar advertisement for five cents. We wanted it to feel like this was real life and that it extended blocks and blocks.

Viola, can you talk about working with Denzel both as an actor and then having him as a director?

VD: Well, Denzel just knows the actor. He knows the process, and you don’t often get that. Sometimes people come in as a director, and they just want the result, and they barely want that to tell you the truth. Sometimes directors barely talk to the actors; they are so focused on the cinematic elements of the movie, getting the shot and getting the lighting right or getting the CGI effects right and all of that, and they just trust that you are just going to do what you do. Obviously, [“Fences”] is not a piece you can do that with. It is a character-driven piece in every sense of the word, and Denzel knows the actor. He gave us two weeks of rehearsal. He is a truth teller, and he is a truth seer. So he knows when something is not going in the right direction, and he will call you on it. But, he knows the word to use to unlock whatever is blocking you. So I think he’s fabulous and he’s a teacher.

DW: Keep going girl!

VD: (Laughing) When Denzel first called me on the phone after we’d just done a reading of the film. He said, “Oh Viola it was so good, wasn’t it?! I’m gonna tell Russell [Hornsby] to lose a little bit of weight and…” I was just sitting there thinking, why is he calling me? And I told him, “Denzel don’t you tell me to lose weight!” He said, “I’m not telling you to lose weight! I can’t believe you would say that.” He was rustling with something and when he came back it was with a word about loving myself and the body that I’m in because I was still going on and on about the weight thing. I just liked that, because what people don’t understand is that so much of what blocks us as actors is so personal. So it just great. Lloyd Richards is another director who was like that, who was a teacher. When a director can give you a word that allows you to feel less tense about yourself, to make you feel like you indeed are good enough before you even get to the work, you can’t ask for anything more than that.

Since all three of you worked together on the stage play, what was it like bringing in the new cast members for the film?

SH: It was very very easy to open up to them. Both of the new people were so respectful of the work and glad to be there. Nothing was taken for granted, coming into the film.

DW: Just so you know the new people are Jovan [Adepo] who played Cory and the little girl.

SH: Saniyyah [Sidney] and Jovan, they both came, and they were so respectful towards the work. Once of the things Mykelti Williamson, Russell Hornsby and I did is we took Jovan out to Greenwood where August is buried. I’d been there a few times, and we took him out to his headstone, and I remembered this tree, and that’s all I remembered. I saw a tree and it was a wrong tree, but Jovan saw this other tree and ran up, and he got there first. For me, it was really a sign. There was so much about this whole experience that proved that the people who were brought to it, were brought to it by forces. I mean they were brought to it by Denzel, but Denzel is such an instinctive kind of person. He’s an instinctive artist and instinctive in terms of his feelings about people. So, it was very easy and Saniyyah, well forget about it. She’s an old soul; she’s been here before.

Speaking about Saniyyah, what was it like finding her in the casting process because she is such a crucial character?

DW: She just had “it.” I didn’t want to audition the kids so much; I just wanted to talk to them because I like seeing how they are because their mothers usually mess them up with practice. So, I’d rather talk to them and see how they respond. I just throw things at them and see how they can hit the ball back, and she was good. I even asked her why she wanted to be an actor and she said, “I’m serious about this. These other little kids they want to play, and I don’t have time for that.” She was very serious about her work and her craft, and she wanted to be good, and she wanted to work on it. So I said, “Ok.” It was as simple as that. She was just right. She just has it.

Continue reading at Shadow and Act.

Image: Fences/Paramount

If you exist outside of the Greek world, and certainly if you attended a predominantly white university as a student of color, Greek life swirls around you.

If you exist outside of the Greek world, and certainly if you attended a predominantly white university as a student of color, Greek life swirls around you.

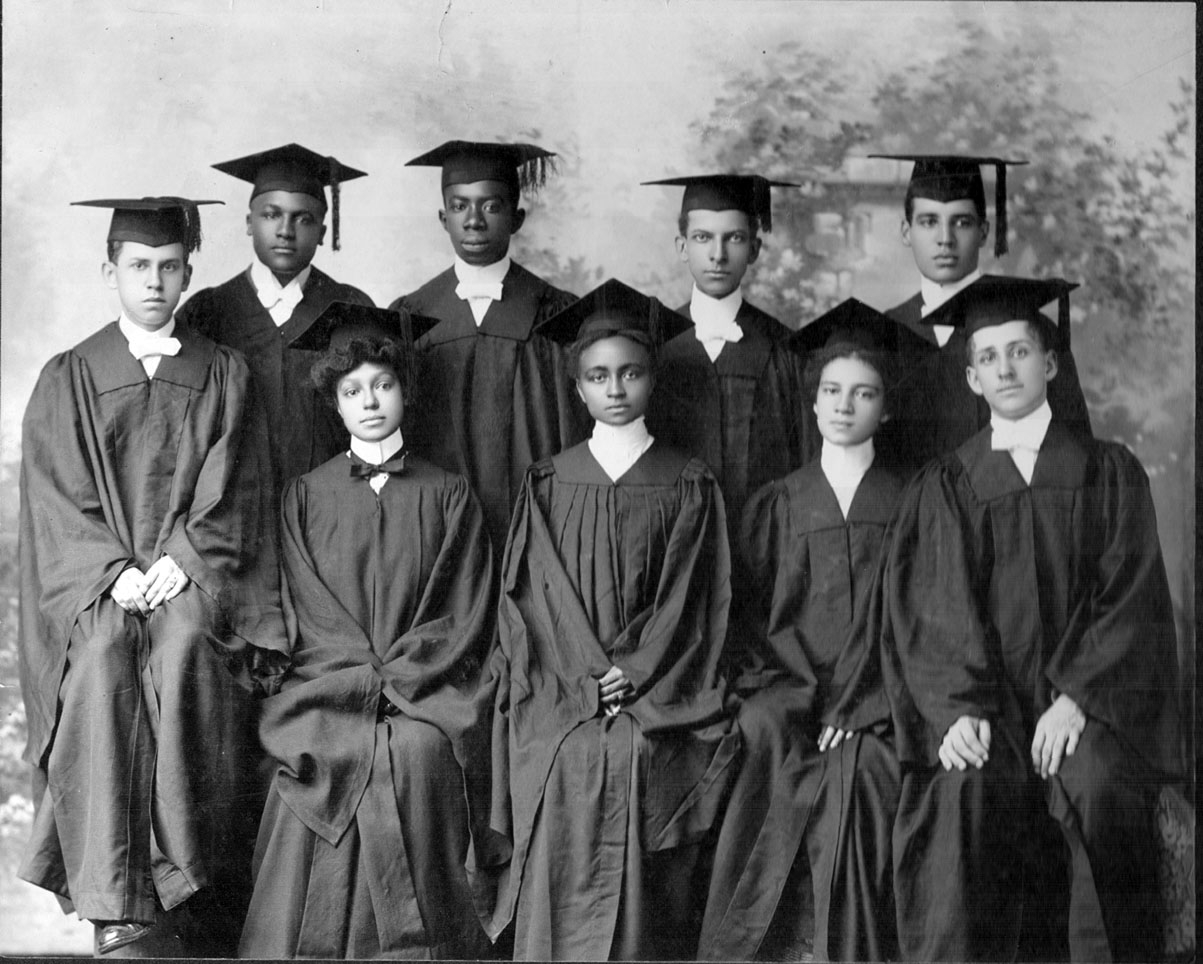

To this day, education is not an inherent right. The effects of segregation are still deeply steeped in the Black community, and unless there is careful nurturing within the family home or by some particularly devoted educators, many Black people in this country have found themselves severely under and uneducated. Despite the lack of resources that are devoted to many public schools particularly in impoverished communities; Black people have always desired the opportunity to learn more about not only themselves but also the world around them. After all, is that not education’s purpose?

To this day, education is not an inherent right. The effects of segregation are still deeply steeped in the Black community, and unless there is careful nurturing within the family home or by some particularly devoted educators, many Black people in this country have found themselves severely under and uneducated. Despite the lack of resources that are devoted to many public schools particularly in impoverished communities; Black people have always desired the opportunity to learn more about not only themselves but also the world around them. After all, is that not education’s purpose? In his spellbinding and heartbreaking Academy Award nominated film, “I Am Not Your Negro,” Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck examines the story that James Baldwin never finished writing. “Remember This House” was to be a sweeping narrative exploring the lives, journeys, and deaths of three pivotal men in our history; Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. An intricate and fascinating narrative, “I Am Not Your Negro,” gives us a view of both Baldwin and Peck’s journeys as Black men in America, encountering racism and violence.

In his spellbinding and heartbreaking Academy Award nominated film, “I Am Not Your Negro,” Haitian filmmaker Raoul Peck examines the story that James Baldwin never finished writing. “Remember This House” was to be a sweeping narrative exploring the lives, journeys, and deaths of three pivotal men in our history; Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. An intricate and fascinating narrative, “I Am Not Your Negro,” gives us a view of both Baldwin and Peck’s journeys as Black men in America, encountering racism and violence. Set in the late 1970’s in the robust and colorfully textured world that is August Wilson’s Pittsburg, “Jitney” is a profound and compelling story about a group of Black men trying to scratch out a living as unlicensed jitney drivers. Threatened by impending gentrification, personal hardships and fractured relationships, Wilson’s first play is a stunning drama about the depths and complexities of Black masculinity.

Set in the late 1970’s in the robust and colorfully textured world that is August Wilson’s Pittsburg, “Jitney” is a profound and compelling story about a group of Black men trying to scratch out a living as unlicensed jitney drivers. Threatened by impending gentrification, personal hardships and fractured relationships, Wilson’s first play is a stunning drama about the depths and complexities of Black masculinity. Returning to their roles six years after the Tony Award-winning revival of August Wilson’s “Fences” stunned Broadway; Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, and Stephen Henderson are at long last presenting the sixth play in Wilson “Pittsburg Cycle” to film audiences.

Returning to their roles six years after the Tony Award-winning revival of August Wilson’s “Fences” stunned Broadway; Denzel Washington, Viola Davis, and Stephen Henderson are at long last presenting the sixth play in Wilson “Pittsburg Cycle” to film audiences. On July 12, 1991, John Singleton’s “Boyz N the Hood” came roaring into theaters. The Black community was feeling the residual effects of the ‘80s crack epidemic. George H.W. Bush was in the White House, and the Los Angeles community was still reeling from the brutal beating of Rodney King by the LAPD four months prior.

On July 12, 1991, John Singleton’s “Boyz N the Hood” came roaring into theaters. The Black community was feeling the residual effects of the ‘80s crack epidemic. George H.W. Bush was in the White House, and the Los Angeles community was still reeling from the brutal beating of Rodney King by the LAPD four months prior.